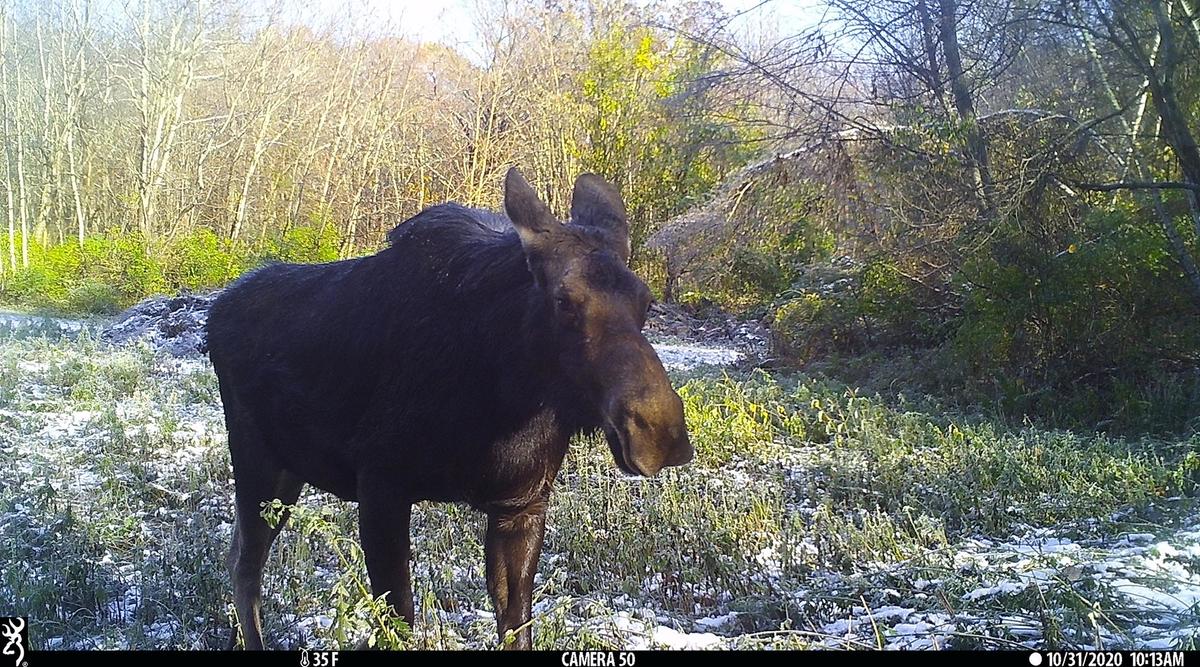

Cary Institute had an unusual visitor last fall when a moose (Alces alces) was spotted on our 2,000-acre Millbrook campus. Trail cameras on our grounds snapped images of the adult female moose during October and early November before she moved off to whereabouts unknown. While at Cary, she hung out in swampy forests and secluded openings, mostly out of sight of people and seemed quite at home.

In North America, moose inhabit parts of Canada and 16 northern US states including NY’s Adirondack region. Moose are not resident in southeastern NY, but may wander infrequently through the area. To our knowledge, last year’s visitor was the first one seen at Cary in modern history.

Moose are the largest living members of the deer family. Adult males, or ‘bulls’, can weigh in excess of 1,500 pounds. ‘Cows’ (adult females like the aforementioned Cary visitor) typically weigh between 400-1,000 pounds. Photos taken by a Cary trail camera demonstrate how much larger even a cow moose is compared with our resident white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus).

Like other males of the deer family, bull moose grow and then shed a new set of antlers each year. Antlers are made of bone, and are one of nature’s fastest growing tissues. Mature Alaskan bull moose may grow antlers more than 75 inches wide and weighing 80 pounds or more. Quite a feat to grow new ones every year.

Besides its size, moose differ from our common white-tailed deer in that a moose’s tail is small and inconspicuous, and they have a large fold of skin under their chin known as a dewlap or bell. The purpose of this dewlap is unknown, but could be a signal used in mate selection or dominance. The nose of a moose is long and bulbous, and the openings in the nose can be sealed shut when feeding under water. Moose have an excellent sense of smell, which helps them located food and water, find mates, and detect predators.

Like deer, moose are herbivores that browse on woody twigs during winter when other foods are scarce. Also like deer, they carefully select which foods to eat based on their nutritional needs. In summer, moose spend a great deal of time feeding on aquatic plants, which provide energy plus salt that is less available in plants growing on dry ground. Ponds also help to cool these large animals when the weather turns warm. Excess heat may be one of the factors that limits the southern distribution of this species, and makes it unlikely it will be more than a passing visitor in our area.

Moose populations have been declining in parts of North America. Declines were once blamed on a parasitic brainworm that lives in but does no obvious damage to deer, but can harm moose. However, we are learning that climate change is more likely to be the culprit.

Warmer winters allow winter ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) to survive and thrive. These ticks feed on moose (and elk and caribou) as their primary host during all life stages. Winter ticks don’t drop off after taking a fall blood meal. Instead, they stay on the moose all winter before dropping off in spring. Thousands of ticks can attach to a single moose, causing hair loss, anemia, and death. Young moose are especially vulnerable, with some 50% of all moose calves in Vermont dying each year from the parasites.

Ticks usually do not kill adult moose but may weaken them and make them more susceptible to predation and cause them to produce fewer young.

Although moose face many threats, protective measures like land conservation could help. By saving land to create corridors of protected habitat, moose and other wildlife can safely move to suitable areas as climate warms. Monitoring efforts are another important tool. By tracking moose numbers and movement throughout New England, managing agencies are working to keep herd densities at a safe level to reduce disease transmission.

Bibliography:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moose#Description_and_anatomy

https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/animals/mammal/alam/all.html

https://www.mammalsociety.org/moose

https://www.northeastwildlife.org/disease/winter-ticks

https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/6964.html

https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/72211.html