Explore acid rain - its causes, effects on ecosystems, and the ongoing efforts to address this environmental issue.

Learn how air pollution from fossil fuels contributes to acidic precipitation and the long-lasting impact on terrestrial and aquatic environments. Discover the history of acid rain research, the Clean Air Act amendments, and why collaborative efforts are essential for a sustainable future.

What is acid rain?

Acid rain, or acid deposition, is precipitation that contains acidic components such as sulfuric and nitric acids. The term ‘acid rain’ encompasses not just rain, but also snow, sleet, fog, dew, and atmospheric gases and dry particles.

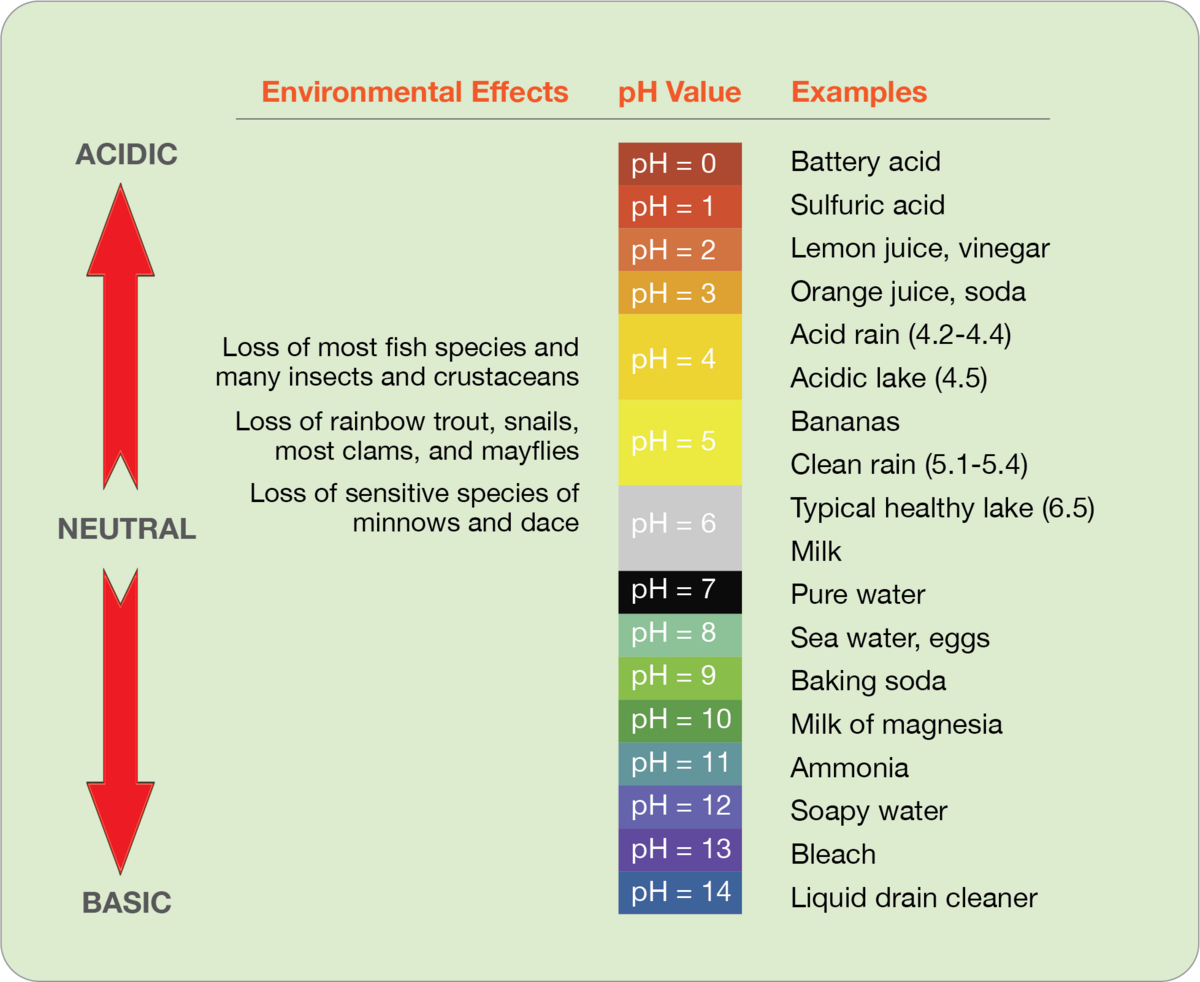

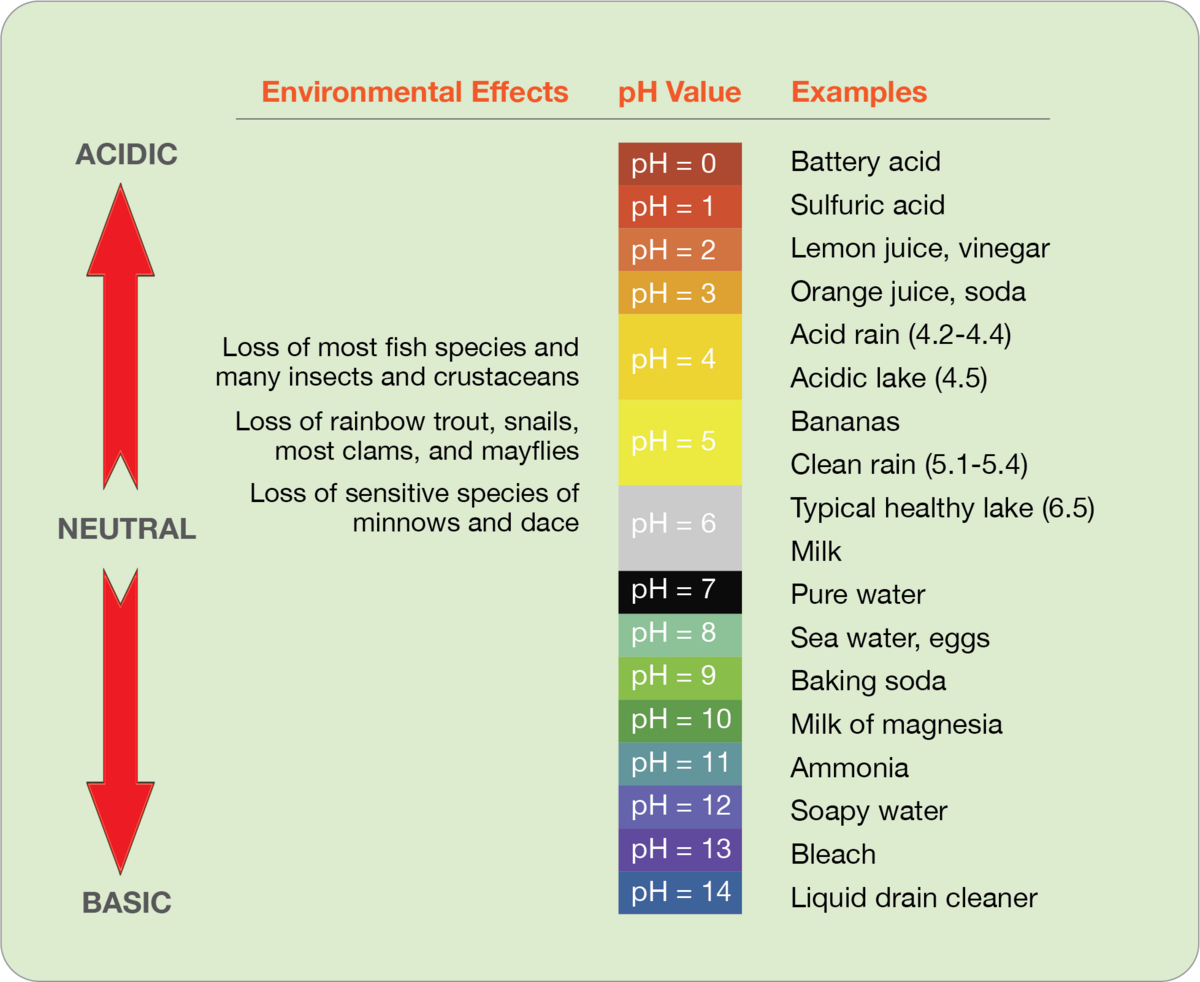

How acidic must deposition be to be considered ‘acid’ rain? On the pH scale, where 7.0 is neutral, and normal rain (which has some natural acidity) is about 5.2, acid rain may register at about 4.5 and even lower, to below 3.0. And with each 1.0 decrease on the pH scale translating to a ten-fold increase in acidity, these values are alarming indeed.

What causes acid rain?

Following years of research, scientists determined that the cause of acid rain is air pollution resulting from burning fossil fuels. Emissions from coal-fired power plants; factories; cars, trucks, and planes; and other sources introduce sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere, where the compounds react with water vapors and are converted to the sulfuric and nitric acids found in acid rain.

Atmospheric pollution affects not only the region where it’s created; it also impacts destinations hundreds of miles away. Researchers found that emissions from industrial smoke stacks in the U.S. Midwest traveled on wind currents and later fell as acid rain and snow in the Northeast U.S. and Canada.

What effects does acid rain have on the environment?

Acid deposition causes widespread damage to terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, negatively impacting lakes, forests, soil quality, plant health, freshwater fish, frogs, salamanders, and other wildlife. In addition to harm caused by the acidity itself, acid rain also disrupts ecosystems by stripping soil of nutrients like calcium and magnesium, and by leaching toxic aluminum from the soil, which then finds its way into nearby waters.

At its height in the U.S. in the 1970s and 1980s, acid rain’s impacts were extensive and, in many cases, so apparent to the average citizen that they were impossible to ignore. Trees in forests were stripped of leaves. Species like the sugar maple and red spruce were devastated. The high acidity of streams and lakes killed adult fish and prevented fish eggs from hatching. Algae and many insects could not survive, which meant peril for creatures in the ecosystem that depended on them for nutrition. Lack of calcium resulted in bird eggs that were too fragile to hatch. Along with these and countless other examples of harm to ecosystems, acid rain also caused visible damage to infrastructure like buildings and bridges, as well as historic monuments, gravestones, and art.

How was acid rain discovered?

The acid rain story began in 1963 in New Hampshire’s Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, where ecologist Gene E. Likens and three colleagues were studying ecosystems through the lens of the forest’s watersheds. In the course of their research, they were surprised to discover water samples with an average pH of 4.1—about 100 times more acidic than they expected (though at the time, they didn’t know what the natural pH of water should be).

With many questions to answer, the research team started by traveling to remote, non-industrialized areas of the world to set up precipitation collection stations. They soon found that their New Hampshire readings (as well as later ones collected in New York’s Finger Lakes region) were actually up to 1,000 times more acidic than those of these new, pristine samples.

Dr. Likens and the team next focused on capturing data points for industrial emissions. In small planes and vehicles, they followed plumes emitted from smokestacks in Ohio and collected air samples. Ultimately, the team determined the process by which these emissions combined with water vapor to create acid deposition.

What was done to address acid rain?

In 1972 and 1974, Gene Likens and his team published their findings and coined the vivid, accessible term ‘acid rain’ to capture the public’s attention and its support for addressing this problem. Their research was the subject of a front-page story in The New York Times, after which the issue quickly gained steam and remained in the headlines throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Dr. Likens—who, in 1983 founded what is today the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies—devoted more than 16 years to raising awareness about acid rain, advocating for solutions with Congress and three U.S. presidents, and responding to industry and political pushback.

Gene Likens ultimately helped secure bipartisan support for the 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act, which included provisions to address acid deposition by requiring industry to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions. The implementation of the Act’s regulations and their positive effects on ecosystems constituted what is widely considered a true environmental success story.

A hearing on the National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program, specifically whether the Program was meeting its Congressionally-mandated goals. Dr. Gene E. Likens provided testimony at 1:58:50.

Does acid rain still exist? Where do we go from here?

Does the success of the implementation of the 1990 Clean Air Act amendments mean that acid rain is no longer a problem? Unfortunately, no. Acid deposition from prior decades has had lingering effects that still must be addressed. Ecosystems damaged by acid rain lost some of their buffering capability, meaning that they are now more sensitive to smaller amounts of pollutants—it takes less acid to cause an equal or greater amount of damage. In addition, the 1990 amendments focused on removing sulfur dioxide, which means that a similar effort to remove nitrogen oxides, the other major pollutant, is needed. And, acid deposition was not and is not a problem limited to North America. It occurs, and must be addressed, in industrialized areas all over the world.

Full recovery of our ecosystems will take a long time. That means that all of us—scientists, policy makers, and concerned citizens—must work together to complete the work of addressing the problem of acid rain.