Who needs males, anyway?

Not the hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), a tiny invasive insect from east Asia that is killing millions of hemlock trees throughout the eastern US.

In its native range, the hemlock woolly adelgid lifecycle includes winged males and females that fly off hemlocks to spruce trees to mate and reproduce. We lack a suitable spruce species in North America, so sexual reproduction is unsuccessful. (Winged individuals fly off and die.) The wingless females reproduce asexually on hemlock trees, making hundreds of genetically identical copies of themselves. The males have become totally irrelevant.

What is the hemlock woolly adelgid and where would I see it?

The hemlock woolly adelgid is a small, aphid-like insect that you can find on the underside of hemlock branches, where it forms small cottony masses on twigs. This white, waxy ‘wool’ is what gives the insects their name. It is secreted as they develop, and it shields the insects from predators and may also keep them from drying out.

Under the telltale white ‘wool’, the insects insert their feeding tube into cells at the base of hemlock needles and feed on carbohydrates, eventually starving the hemlocks of this vital energy supply. The ‘wool’ is easy to spot by looking at the underside of hemlock twigs in the late fall, winter, and spring. In mid-summer, the insects enter a dormant, inactive state until they become active again in the fall.

In North America, hemlock woolly adelgids are wingless so they must rely on other animals to spread. An early larval stage, called a ‘crawler’, can scramble around on branches and can also hitch a ride on birds and other animals, including people. This is likely the main way that the insects spread. People also spread the insect by moving infested plants from natural settings or nurseries, which can help infestations expand quickly over large areas.

How was the hemlock woolly adelgid introduced?

It is suspected that hemlock woolly adelgid was introduced to the eastern US on Japanese hemlock trees imported for an ornamental garden near Richmond, Virginia in 1911.1 At that time, Japanese gardens were very fashionable among the wealthy, and there were no controls on plant importation. A small hemlock woolly adelgid infestation was discovered near that site in 1951, but nothing was done to eradicate it.

How widespread is the pest?

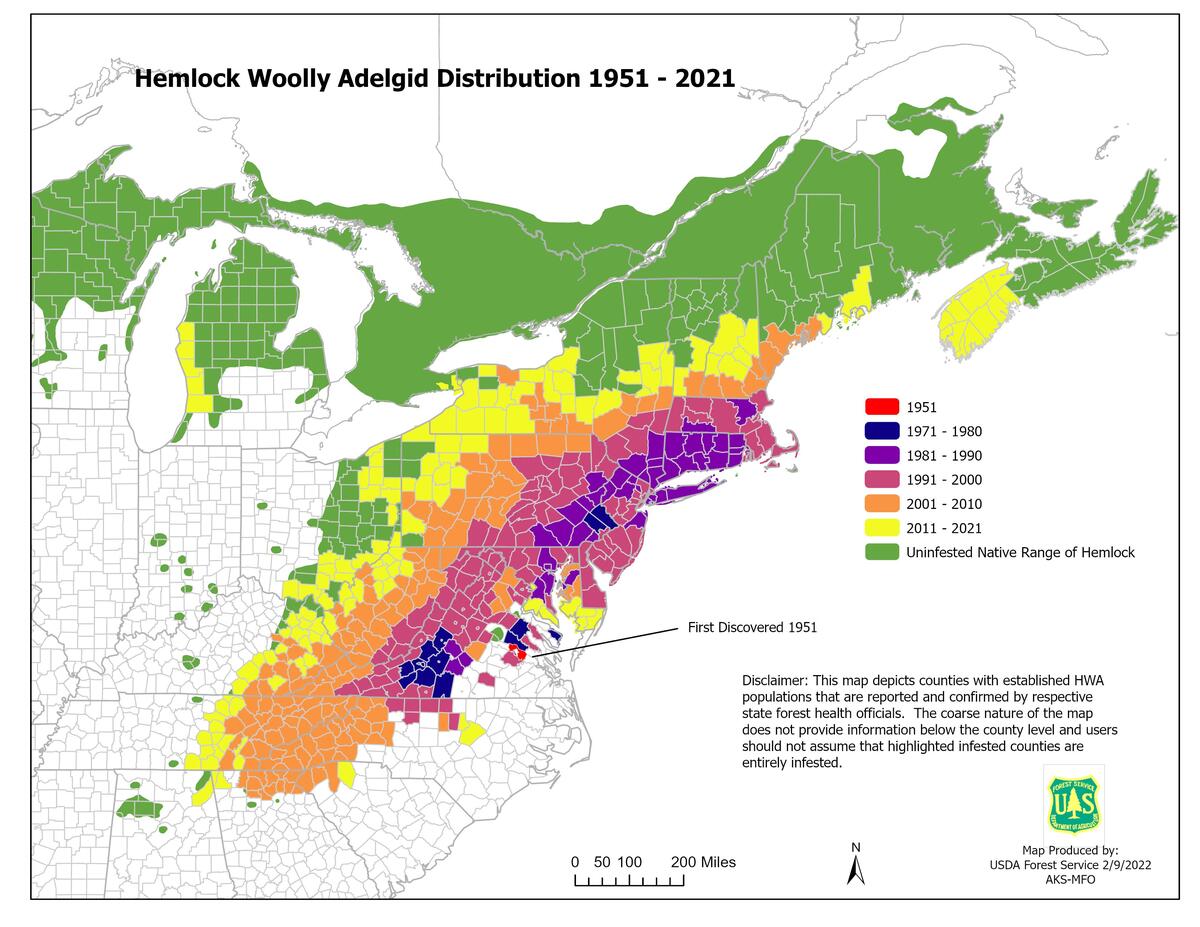

Over the next several decades, the insect spread slowly until it reached the hemlock-rich Appalachian Mountains in the 1980s. At this point, it began to spread rapidly north and south, infesting both eastern and Carolina hemlocks. In the southern Appalachians (notably in Great Smoky Mountains National Park), old growth hemlock stands succumbed quickly, and most hemlock trees died within a few years after they were first infested. Similar rapid mortality of hemlock occurred later in the mid-Atlantic states and coastal areas of southern New England.

The range of eastern hemlock extends north into Canada and west into Minnesota. The insect has not yet reached the entirety of this range. The leading edge of the invasion is currently along a line from southern Maine through central New Hampshire and Vermont, and into the southern Adirondacks of New York. The insect has also invaded southern Nova Scotia, and has moved west as far as Michigan.

As the pest has moved north, its rate of spread has slowed, and the time it takes to kill hemlock trees has lengthened. For instance, here at Cary Institute in southeastern New York State, hemlock woolly adelgid first arrived in 1998, but widespread death of hemlocks did not occur until after 2010, and some hemlocks are still surviving as this piece is written in 2022.

Climate change and the spread of hemlock woolly adelgid

The hemlock woolly adelgid is sensitive to cold winter temperatures. Low temperatures in the range of -10oF will kill most of the insects, but this depends on their cold hardiness as conditioned by previous low temperatures.2 With two generations per year, populations can rebound quickly, but repeated winter kill slows the growth and spread of the pest.

There are two troubling trends that do not bode well for the future of hemlocks. First, hemlock woolly adelgid populations in the north have become more cold-tolerant than those in the south.3 This suggests that the insect is evolving greater cold tolerance as it moves northward. Second, climate change is causing milder winter temperatures. Northern regions simply don’t see the number of very cold winter nights that they did in the past. Both trends will likely allow the hemlock woolly adelgid to continue to move northward and westward, albeit slowly, and eventually reach the entire range of eastern hemlock.

How does hemlock woolly adelgid affect forest ecosystems?

Hemlock woolly adelgid is the biggest threat to hemlock trees in the eastern US, and has the potential to nearly exterminate the entire hemlock (Tsuga) genus in this region. Hemlock loss reverberates through the entire forest ecosystem. They are one of the longest-lived trees in eastern forests, and when they are dominant, they create unique stands that are dark, cool, and moist, with very little understory. When hemlocks die and other tree species replace them, those conditions disappear. The opening of the canopy can allow successional trees and invasive plants to establish.

Some animals rely on hemlocks for food and shelter. In southern New England, black-throated green warblers, Blackburnian warblers, and Acadian flycatchers are associated with hemlock forests; these songbirds decline when hemlocks die.4 Deer often use hemlock groves as yarding areas in the winter. Hemlocks also shade streams, keeping them cool. Losing hemlocks along streams degrades habitat quality for fish that need cool water, such as the brook trout.

What can we do about it?

There are treatments to control hemlock woolly adelgid on individual trees (for instance, a tree in a yard) through both systemic insecticides and surface-applied insecticides such as dormant oils. These require repeated applications over the life of the tree, so they are expensive and impractical to implement over large areas.

To try to save hemlock trees over broad areas, several research groups are developing ‘biological controls’. These methods involve releasing insects that prey on hemlock woolly adelgid.

The predator insect needs to be able to tolerate cold temperatures when hemlock woolly adelgid are active in the winter. Several insect predators may be needed to attack hemlock woolly adelgid at different stages of its life cycle, and precautions must be taken to ensure that introduced predators do not harm native plants or insects. So far, biological control efforts have achieved only modest success.

The future of hemlock in the eastern US does not look bright. Hemlock woolly adelgid is on track to spread over the hemlock’s entire range, killing off one of the most unique and important trees in northern forests. In the long term, biological control methods and breeding resistant varieties of hemlock offer some hope, but neither seems able to provide significant help in the near future.

To prevent future ecological disasters like the hemlock woolly adelgid invasion, the US (and all countries) needs to impose more stringent controls on the international trade of live plants. Cary Institute’s Tree-Smart Trade program seeks to develop and communicate smarter trade policies that will help prevent the importation of damaging forest pests and diseases.

References

1 Havill N.P. and M.E. Montgomery. 2008. The role of arboreta in studying the evolution of host resistance to the hemlock woolly adelgid. Arnoldia 65:2-9.

2 Elkinton, J. S., J. A. Lombardo, A. D. Roehrig, T. J. McAvoy, A. Mayfield, and M. Whitmore. 2017. Induction of cold hardiness in an invasive herbivore: The case of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Hemiptera: Adelgidae). Environmental Entomology 46:118-124.

3 Butin, E., A. H. Porter, and J. Elkinton. 2005. Adaptation during biological invasions and the case of Adelges tsugae. Evolutionary Ecology Research 7:887-900.

4 Tingley, M. W., D. A. Orwig, R. Field, and G. Motzkin. 2002. Avian response to removal of a forest dominant: Consequences of hemlock woolly adelgid infestations. Journal of Biogeography 29:1505-1516.