In January, Michigan is a province deep in the Kingdom of Ice.

Looking through silvery feathers of frost on the window glass, I see big flakes of snow swirling against a gray sky. The air is filled with the sounds of snow shovels, ice-scrapers on car windows, and crunching footsteps on packed snow.

Roads and driveways are covered in crusty, rutted ice. Out in the countryside, flocks of gray and brown winter birds rise and fall over snow-covered fields. And if there isn’t any snow, the earth itself is frozen solid, as hard as iron. The solitary figures of ice-fishermen dot frozen lakes, and ice rattles in the surf of the big lakes.

You might deny being part of the Kingdom of Ice – Michigan is more about summer sunshine than it is about ice, you say – but our language betrays us. If we are not people of the ice-country, then why do we have so many words for what is just a single substance: frozen water? Ice, snow, slush, powder, drifts, flurries, blizzards, sleet, hail, freezing rain, frazil, frost, black ice, white ice, candle ice, skim ice, anchor ice, rime, and hoarfrost. And these are just the words I could think of off the top of my head, without going to the dictionary.

Now, how many words can you think of for sunshine?

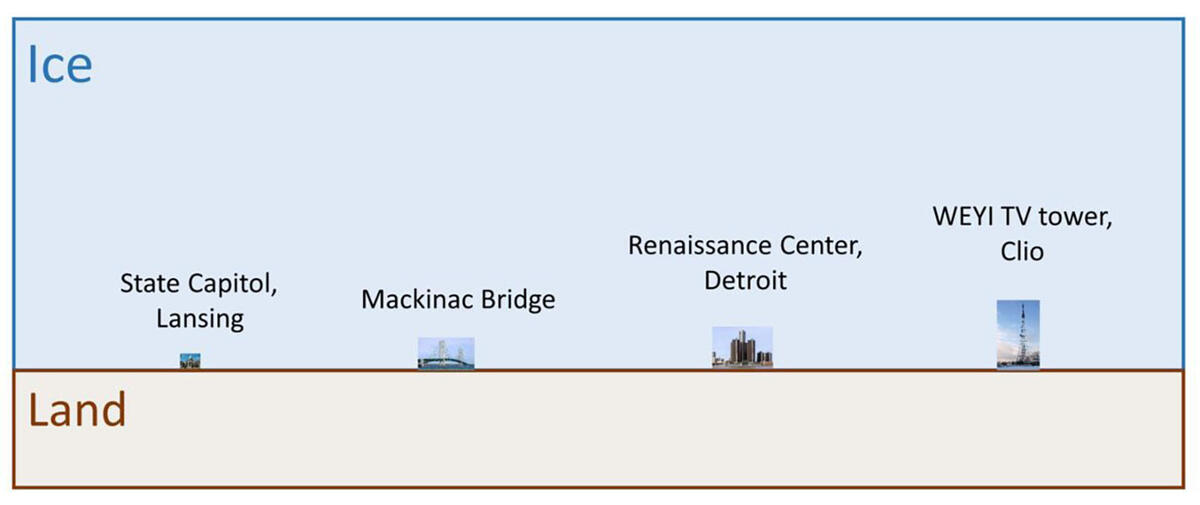

But even more fundamental than the ice we see every day during our long winters, we live in a landscape that was shaped by ice. For the last 2 million years, immense ice sheets repeatedly grew and spread across Michigan, and then receded, as the climate cooled and warmed. As recently as 20,000 years ago, the whole state of Michigan was submerged in an ocean of flowing ice more than a mile deep.

As these ice sheets advanced and then melted, they built the place that we know today as Michigan. Glacial ice gouged away at river valleys and soft spots in the rock to produce the Great Lakes and steep-sided beauties like Torch Lake. Then, they deposited this excavated material elsewhere to build new landforms.

The hills of Ann Arbor are end moraines – piles of debris accumulated when the front edge of a glacier paused in place. The charming hills and countless lakes and ponds of the Irish Hills southeast of Jackson were left by a dying glacier. The region’s lakes lie in the basins left when huge ice cubes submerged in a plain of sand and gravel melted away, and its gravelly hills are the remnants of deposits accumulated between walls of ice, long since gone.

The scale of excavation and construction by the ice sheets is almost beyond comprehension. Suppose that some billionaire, instead of shooting himself into outer space, decides to build us another Lake Superior. He hires a big crew that each day can excavate a volume as large as the inside of the University of Michigan football stadium.

They work 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year, until 52,000 years later – voila! – they’re done.

All this material excavated from Lake Superior and other places had to go somewhere, and a lot of it was used to remodel Michigan. Most of the Upper Peninsula is covered only by a thin layer of glacial debris, but almost all the Lower Peninsula is covered by more than 50 feet of glacial deposits. Most of the region between Grand Rapids and Traverse City is covered more than 300 feet deep by sand and gravel left by the glacier. In some places these deposits are more than 800 feet thick.

It’s hard even to imagine what the land looks like under all that debris, or what it must have looked like before the glaciers remodeled the state. I doubt we’d even recognize it as Michigan.

So in the same way that you might say that you live in a Frank Lloyd Wright house (lucky you!), we can say that we live in a landscape built by ice (lucky us!). And just as you can recognize a Frank Lloyd Wright house by its telltale design elements (strong horizontal lines, lots of glass, repeated use of simple geometric designs), you can recognize a glacial landscape by the abundance of large and small lakes, rolling hills, plenty of sand and gravel and not so much exposed bedrock – all of the things that you think of as Michigan.

All over the world, we can recognize the work of that same great builder in the steep-sided lakes of the English Lake District, the sandy, lake-filled plains around Berlin and the landscapes of Scandinavia.

You might wish that you lived in the Kingdom of Sunshine and Warmth. But if you live in Michigan, you may as well admit that you are a citizen of the Kingdom of Ice and enjoy the beauty of our country.

Originally published in the Great Lakes Echo 1/10/22.