Ashok Jacob is a 2025 participant of the Catskill Science Collaborative Fellowship Program, coordinated by Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies.

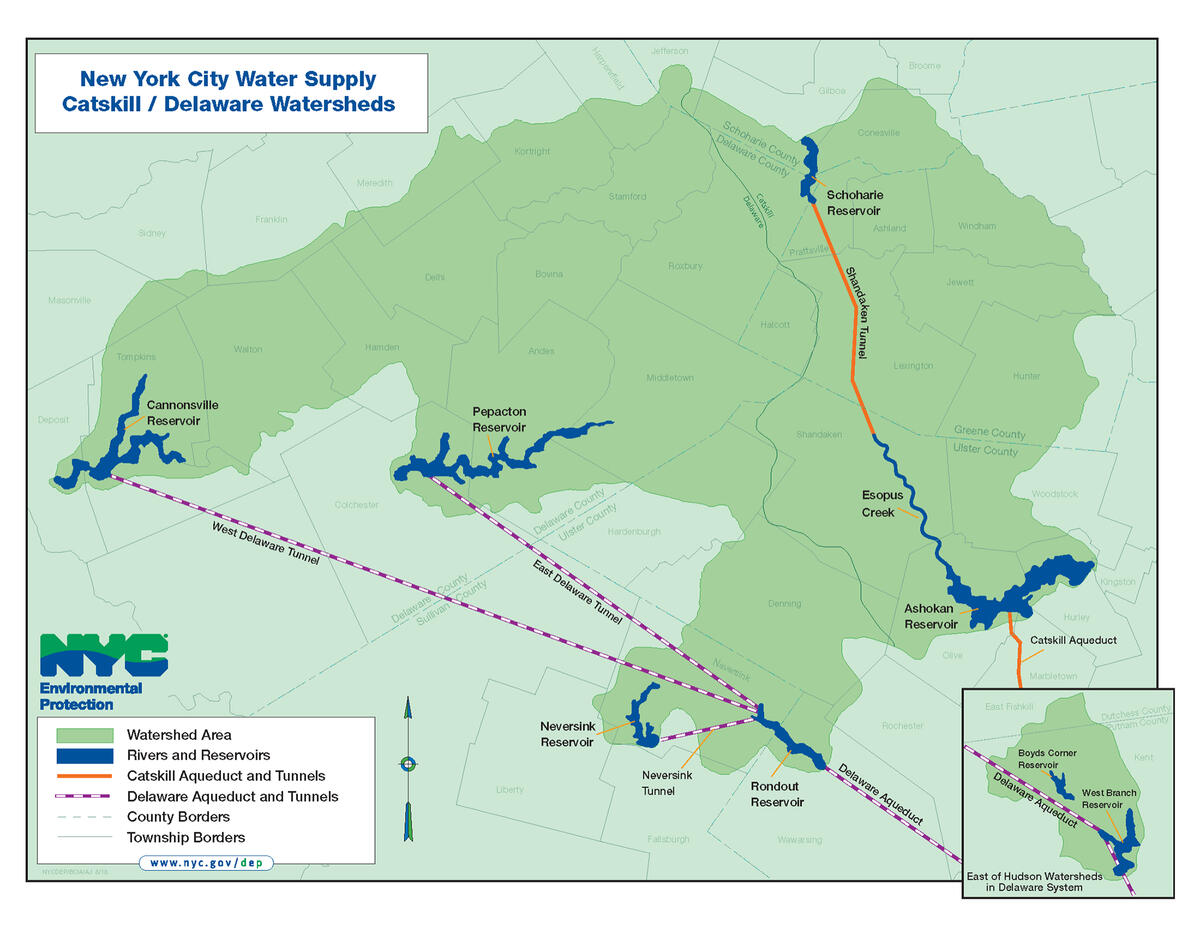

New York City’s tap water is famous — crisp, clean, and often called the “Champagne” of drinking water. Locals even say it’s the magic ingredient in the city’s bagels and pizza. But where does this pristine water come from? The answer lies 125 miles northwest of the city, in the largely forested Catskills-Delaware watersheds. Here, the City of New York protects the source of drinking water for 9 million people through careful conservation, avoiding the need for costly filtration. This summer, I worked with the Catskill Science Collaborative and New York Department of Environmental Protection to study one of the most important protection measures: tree and plant cover along streams — also called riparian buffers. Our study highlights areas where more protection is needed.

Planted along stream banks, these green strips protect streams from sediment, nutrients, and pollutants that can flow from nearby farmland, roads, and other human activities. During a rainstorm, when you see water trickling around the roots of trees and flowing gently between swaying grass, a bigger process is at play. Plants slow down the water, and allow it to soak into the soil, where it is filtered. Riparian buffers amount to 61% of NYC’s stream management programs, with the lowest cost per mile for taxpayers. The cool shade, rich biodiversity, and recreational opportunities they provide are added benefits!

Programs like the Catskill Streams Buffer Initiative and Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program have been central to planting and maintaining these buffers. The current metrics of success have been ‘number of projects’, ‘miles planted’, and, of course, improvements in water quality. But buffers don’t yet cover all of the watershed, and budgets are limited, so we wanted to ask: Can we prioritize areas where the next buffers could be planted, aiming for the “lowest-hanging fruit”? With spatial datasets showing current buffers and the areas most at risk of erosion, it turns out we can!

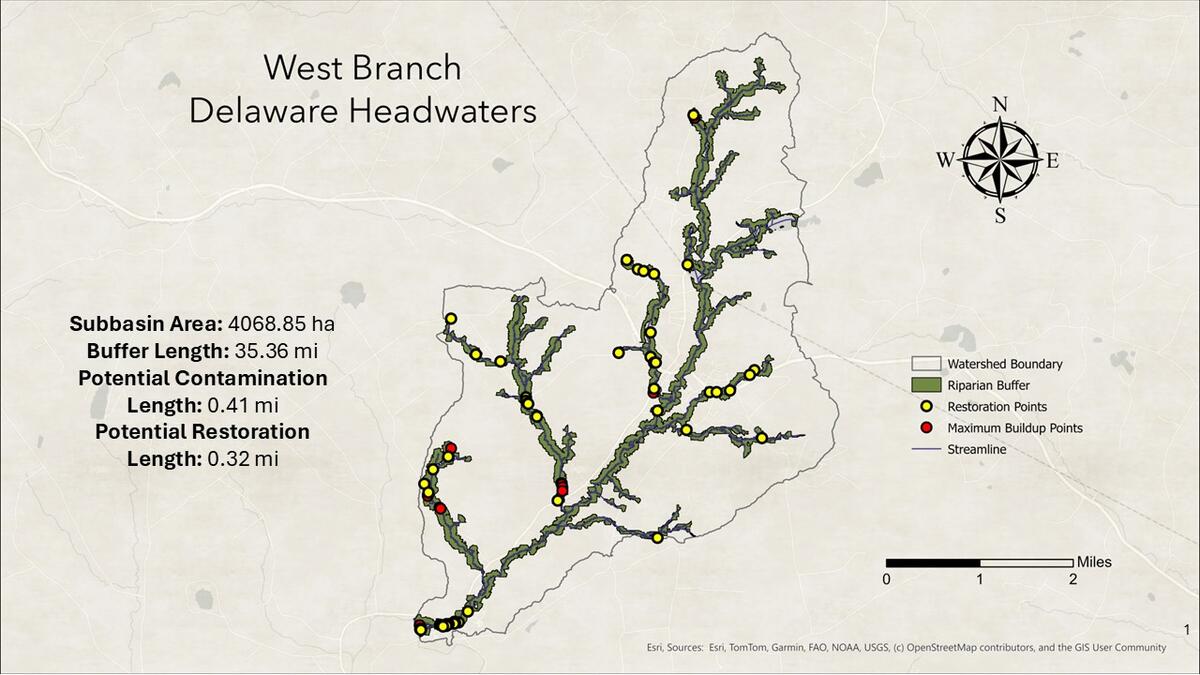

For our study, we focused on the Cannonsville watershed in Delaware County. We looked at land up to 330 feet from the stream banks and divided it into approximately 33-foot parcels. For each parcel, we considered land use (agriculture, urban, conservation, or water), rainfall intensity, slope length, and steepness. From this, we estimated the potential for soil and nutrients to wash into the streams. We also mapped the existing plant and tree cover that helps block that flow. Overlaying these maps revealed which areas are well-protected and which are vulnerable to pollution.

Below are the results for West Branch Delaware Headwater, a relatively large sub-watershed in the northeast of Cannonsville, that drains to the West Branch Delaware River near Hobart. We found areas that are vulnerable to pollution due to lack of buffers, and areas where buffers exist, yet the stream pollutants push through because the buffers aren’t wide enough. We are repeating this process for all the sub-watersheds in Cannonsville. This will help NYC prioritize where to place new tree and plant cover, and at what width. We can also easily extend the analyses to other parts of the Catskills, making it a powerful planning tool.

It’s fascinating to see how New York delivers clean, clear water to millions of people without costly filtration — thanks to upstream conservation in the Catskill-Delaware watersheds. And now, with the identification of where buffers should be prioritized, we can get more value for every dollar invested in conservation in the Catskills!

Ashok Jacob is a PhD student at Penn State studying the effectiveness of riparian buffers in the Catskill Watershed to improve water quality and ecosystem services. In collaboration with NYCDEP and his advisor, Dr. Cibin Raj, he is developing quantitative metrics, spatial maps, and geospatial tools to support NYCDEP’s water quality conservation efforts.