A student contribution to the REU blog.

I ran between two worlds as a kid. One world was green; it was wild and raw. It was an imagined landscape in the Amazon rainforest or the trenches of the deep ocean. In this world, I subconsciously narrated my every movement to the timbre of David Attenborough, which I could attribute to watching Planet Earth on repeat.

The other world was ten feet beyond the TV set that shaped my fantasies. It was the heathered grey of an Atlanta cityscape, void of rainforest and ocean. It was my reality. I was far from where I wanted to be. At a young age, I knew I wanted to be immersed in the outdoors doing field research. Here is what I did not know: the outdoors is not as universally welcoming as nature documentaries paint it to be.

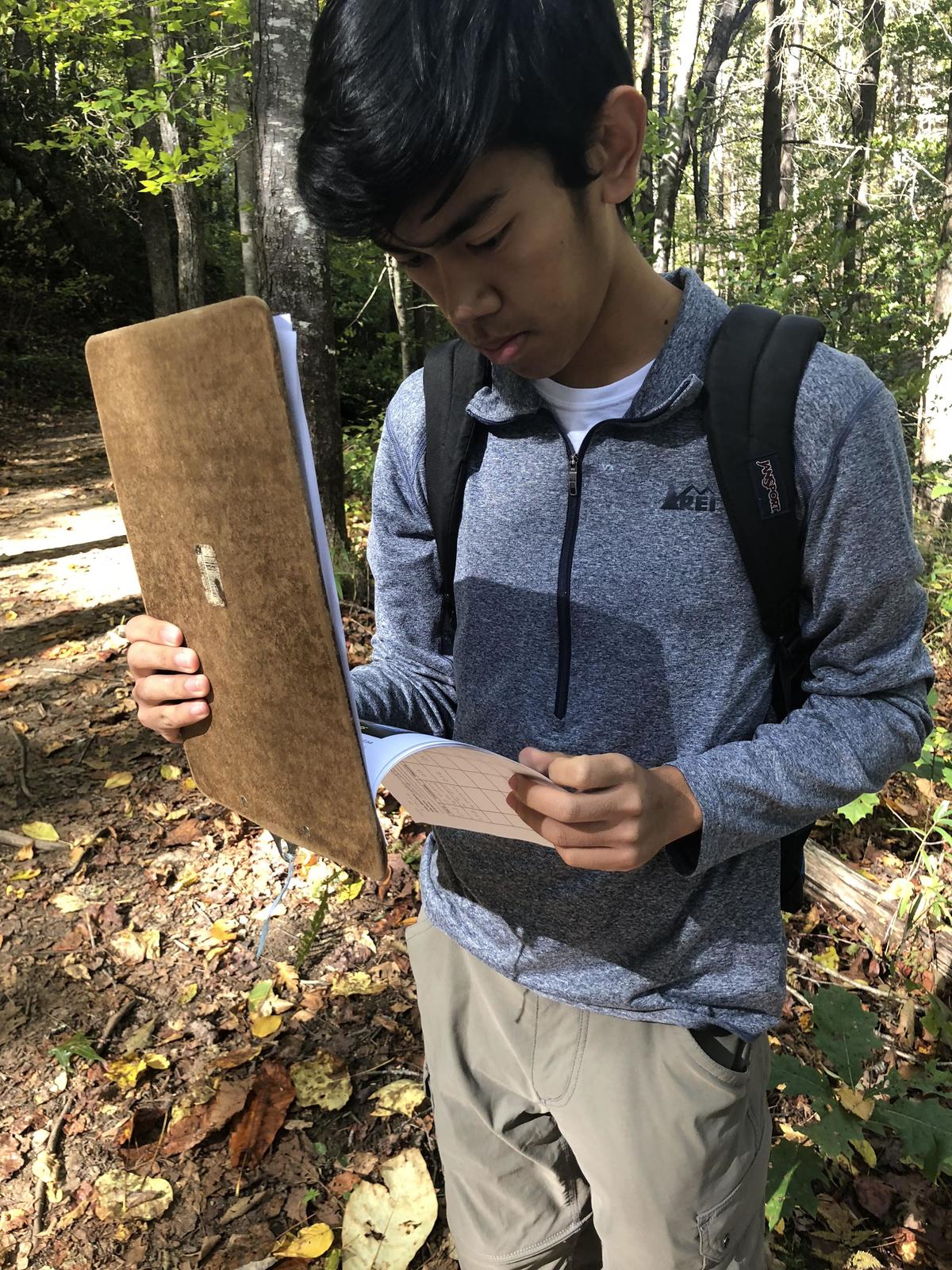

I moved to a small town in the Appalachian Mountains when I was 12, trading tall corporate buildings for canopies of tulip poplars. In high school, I joined a research program and played out my childhood dream of conducting field research. I got to ask questions about the biologically diverse organisms of the Appalachians: Are local trout streams at risk of succumbing to the whirling disease parasite? Can endemic spray cliff plants solve antimicrobial resistance? How can we save the endangered green salamanders? My research took me through freezing waters and down wild cliffs in search of scientific discovery.

Everything seemingly fell into place. I was no longer running after the fantasy I had as a kid. But I started a new race, one that came with an uncomfortable realization: the outdoors was not made for me. Cultural, historical, and socioeconomic barriers disproportionately favor affluent, straight, and white individuals in outdoor spaces. I am a gay Vietnamese American from a low-income family. I feel an incessant pressure to assume a certain identity that is not my own. I am still running between two worlds today.

Unsettling is the lack of welcoming spaces created for the true diversity of people who are enthusiastic about the outdoors or who want to pursue a career in nature-centered STEM fields like ecology or environmental science. I am always reminded that I am entering a field of study that lacks diversity. The outdoors industry plasters marketing material almost exclusively with white models. National parks and forests were created under white racial frames which can be seen in the lack of minority attendance today. Outdoor recreation – and often research – require expensive equipment and clothing that are not accessible to all. When I think of these things, I cannot help but feel buried emotions of discomfort, disappointment, and a lost sense of self.

Despite the evident problems with diversity that exist in outdoor spaces and fields of study, I take care to remind myself of all the things that make the outdoors beautiful and remember why I became obsessed with nature many years ago. One of these beautiful things is Vochysia ferruginea – a tropical tree found in Panamanian rainforests that bears radiant Tuscan-yellow flowers and is one of the tree species I am studying in my Cary REU project this summer.

People representing minority identities are in a perpetual race to let others know that they exist and that their research and contributions matter. I eagerly await the day when we can stop running and savor the beauty of the outdoors, unencumbered by barriers linked to our identities. I envision the outdoors and nature-centered STEM fields as spaces where minorities can be comfortable, authentic, and wholly themselves. These are spaces that invite and uplift people representing all skin colors, sexual identities, genders, and socioeconomic backgrounds. These are spaces where diversity in people parallels that of the flora and fauna of the Panamanian rainforests.

After finishing the Cary REU program, I hope I can share my narrative to inspire the future generation of underrepresented ecologists – this time, not using David Attenborough’s voice, but my own.

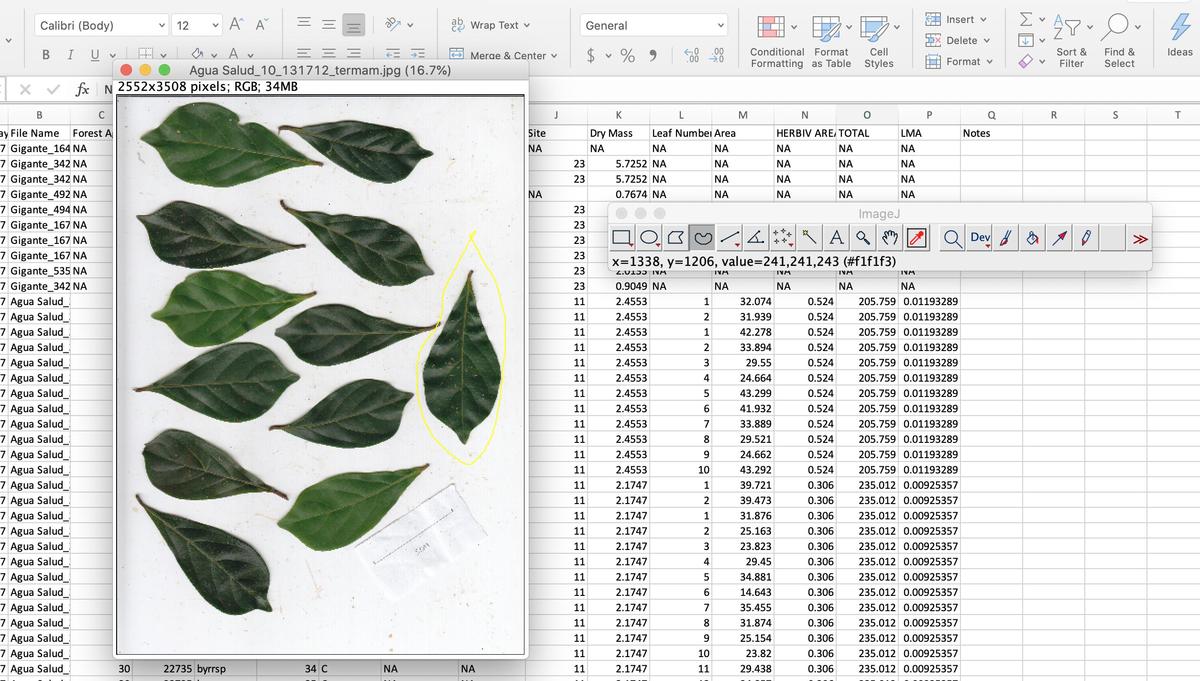

John Nguyen, a student at Columbia University, participated in Cary Institute's 2020 Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program. This summer, John worked with Cary Research Fellow Sarah Batterman, Cary Postdoctoral Fellow Michelle Wong, and University of Leeds PhD Researcher Wenguang Tang to study effects of nutrient limitations on tropical carbon sinks.