Ryan Schmidt is a 2025 participant of the Catskill Science Collaborative Fellowship Program, coordinated by Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies.

Eastern hemlocks are a foundational tree species in New York’s Catskill Mountains, providing food and habitat for many species, including animals, birds, fish, and amphibians. But they are facing a significant threat from the hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive insect that feeds on sap at the base of their needles. This feeding weakens the tree by interrupting its ability to transport nutrients and perform photosynthesis. Over time, this can kill mature hemlock trees and transform the ecosystems they help create.

This summer, as part of a Catskill Science Collaborative Fellowship, I have been fortunate to travel across the Catskills to measure how hemlock health varies from place to place, and how other invasive species may establish themselves, depending on the condition of the hemlocks. This work is part of my graduate capstone research at Pace University, under the advisorship of Dr. Matthew Aiello-Lammens.

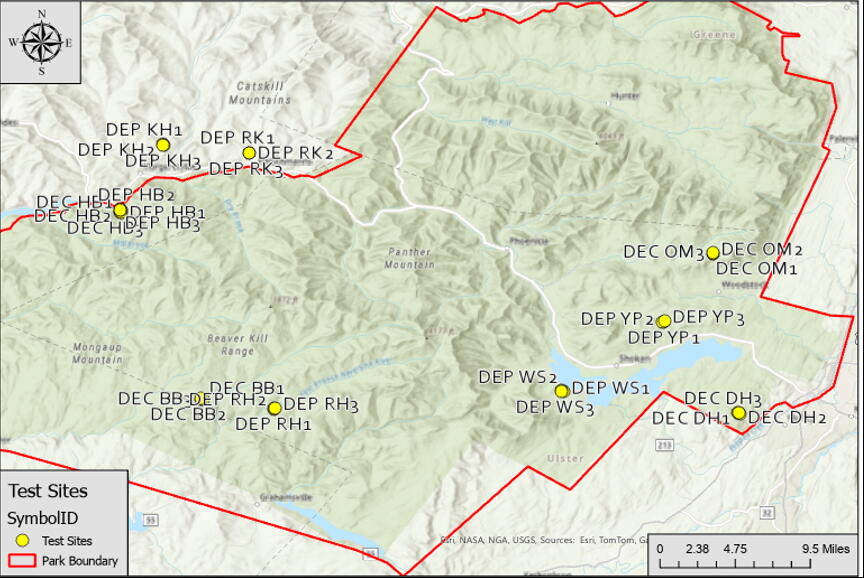

The sites I am studying are based on locations identified in The Nature Conservancy’s 2014 report on managing hemlock woolly adelgid in the Catskills. My research is focused on sites that are accessible through public or recreational land, and that represent a range of adelgid impacts, from severely impacted to healthy stands. I collect data on each tree within my plots, including diameter at breast height, percentage of canopy coverage, percentage of understory vegetation, the presence or absence of adelgid, and an overall health rating for each hemlock.

Early visits showed that plots with greater hemlock woolly adelgid infestation had thinner canopies and denser understory growth. These understories were often dominated by non-native plants such as Japanese stiltgrass and barberry. With less canopy cover, more sunlight reaches the forest floor, creating conditions that favor the establishment and spread of invasive species.

It is important to learn about these patterns because the loss of hemlocks could change Catskill forests, impacting everything from soil chemistry to stream temperature. In the best-case scenario, adelgid spread could be slowed by management measures and naturally cold winters, allowing some stands to survive and sustain native ecosystems. In the worst scenario, a broad reduction in hemlock might let pests and invasive species establish themselves, disrupting the structure and function of these forests.

My Catskills fieldwork has been very fulfilling, even though some sites were harder to get to than others. Traversing streams and being surrounded by hemlocks in healthy groves has been an exciting and distinctive work experience, and the information I gather will help state conservation partners better understand the biological effects of adelgid infestations and develop management plans for hemlock-dominated forests.

To determine conditions that promote resilience, the next steps will involve evaluating patterns across all sampled sites to examine how canopy loss, adelgid quantity, and invasive plant presence interact. I hope my research will assist future conservation and restoration initiatives to maintain the health of the Catskill forests for future generations by tracking how these ecosystems change over time.

Ryan Schmidt, a master’s student in environmental science at Pace University, is conducting research on the ecological impacts of the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) in the Catskill region. His project evaluates how HWA infestation affects tree canopy structure by examining branch density across varying levels of infestation. Additionally, Ryan is investigating potential associations between HWA presence and the establishment of other non-native invasive plant species. This work contributes to a broader understanding of how invasive species reshape forest ecosystems.